The story

Paul St George’s Discovery

Some years ago an artist by the name of Paul St George happened upon a packet of dusty papers in a trunk in his grandmother’s attic. On further inspection he discovered that they had been the property of his great-grandfather, an eccentric Victorian engineer, Alexander Stanhope St George.

Paul began to read through the papers and discovered a veritable treasure trove: diaries, diagrams, correspondence, scribbled calculations, and even one or two photographs. At first, Paul felt a detached interest in this first hand account of social and cultural history. But as he read on, he became more and more absorbed, until, with a sudden thrill, he realised that these papers could have a greater significance than was at first apparent.

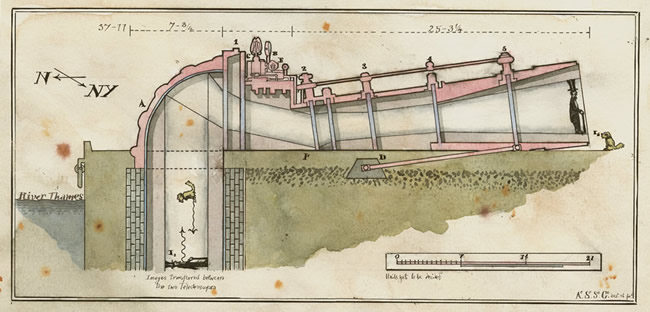

The notebooks were full of intricate drawings and passages of writing describing a strange machine. This device looked like an enormous telescope with a strange bee-hive shaped cowl at one end containing a complex configuration of mirrors and lenses. Alexander seemed to be suggesting that this invention, which he called a Telectroscope, would act as a visual amplifier, allowing people to see through a tunnel of immense length… a tunnel, the drawings implied, stretching from one side of the world to the other.

The idea of the Telectroscope seemed too outlandish to be possible and yet there was something in the scribbled notes that had the ring of truth about it. Despite the many gaps and inconsistencies, Paul began to piece together his ancestor’s remarkable story…

Alexander Stanhope St George

Alexander Stanhope St George was born in London on 8th July 1848 to a British father and Sierra Leonian mother. Alexander was the first of seven children, of whom only three others (Samuel, Grace and Charlotte) survived to adulthood. Details of most of Alexander’s childhood and youth are vague, although Paul St George did make one fascinating and significant discovery.

In November 1857, aged nine, Alexander had been taken to Millwall to see the attempted launch of Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s Great Eastern, the world’s largest steamship. The image of Brunel standing proud and imperious in front of the launch chains is famous, but few people have seen the photograph in full. In the original image, the young Alexander Stanhope St George can be seen, sitting over to one side, clearly revelling in his proximity to the celebrated engineer. Throughout the rest of his life, Alexander referred often to Brunel as his greatest inspiration.

After studying at Edinburgh University, Alexander sought out employment with some of the most eminent engineers of the period, eventually working alongside Joseph Bazalgette on the Chelsea Embankment, John Wolfe-Barry on the District Line of the London Underground and Sir John Hawkshaw on the Severn Tunnel.

The first signs of Alexander’s determined and somewhat impatient nature can be seen in his diaries of this period. In September 1878, he wrote: “I ask you, how much longer can I stand by and watch these old men make their repeated mistakes? There is no alternative but to make my name through my own endeavour: alone.”

The Idea is Born

According to his diaries, Alexander travelled to New York in 1884 to see the newly completed Brooklyn Bridge. He departed from Liverpool on the SS Adriatic of the White Star Line on an uncomfortable voyage of around 10 days’ duration. Alexander was hugely impressed by the monumental bridge, writing in his journal: “Never have we engineers come so close to the work of God. This construction shows skill, ingenuity and audacity… and it far outstrips the so-called achievements of the fools for whom I have been working.”

The return journey was rougher still and in a terrifying storm, supplies were lost overboard. When the ocean was calm once more, the captain sent three small boats ashore at an island to gather food and fresh water. Alexander volunteered to go ashore and help and although his description of this incident is patchy, it is clear that this strangely fortuitous detour, combined with his experience in New York, formed the catalyst for his grand scheme.

Alexander began to explore the possibility of digging a transatlantic tunnel, using the island as the centre of operations from which the tunnel would run in both directions. Following his terrible experiences of sea travel, his first impetus for the tunnel was to enable a more convenient form of transport. However, he soon came to see that travel through the Earth could be just as lengthy and uncomfortable as travel across the sea. Digging a tunnel large enough to move many people and all the associated luggage and provisions would simply not be viable.

But this did not deter Alexander. Instead, his thoughts turned to the possibility of “travelling” across the ocean without actually moving. What, he imagined, if one could see all the way to New York without having to leave London? He began to sketch out an idea for a “device for the suppression of absence”, a powerful optical machine which, if installed at both ends of the tunnel, would magnify the view through it.

Digging

Back in London, in the early stages of what was to become an obsession, Alexander continued to work on the design of the optical device – which he called a Telectroscope. Having worked on tunnelling projects – albeit of a less ambitious nature - with some of the great engineers of the age, Alexander was less troubled by how he would construct the tunnel than by the optical device, but the fact remained that the latter would mean nothing without the former.

Alexander was determined to return to his island to commence digging and not even the birth of his first child could dissuade him. He spent much of the next two years attempting to raise the money to realise his project and eventually, by 1890, had accumulated enough to set off with a workforce and tools to begin digging.

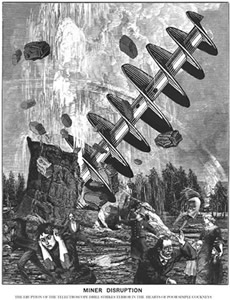

Initially, at least, work went well. A shaft was sunk, deep below the island, ending in an excavated cavern from which men tunnelled out in both directions at once. There was a great spirit of adventure and optimism and despite Alexander’s reluctance to reveal too much about his project, news began to leak. This resulted in some high profile visitors to the island and some news coverage, including a mocking cartoon that was published in Punch.

A Tragic End

The first major blow came on 5th March 1892 when the ocean breached the tunnel roof. Fifteen men were lost. Alexander wrote: “The loss of life is a terrible cross to bear and yet, for the greater good, we must persevere.” After this, however, the project was beset by problems both large and small. Gradually, the workforce dwindled and Alexander was forced to draft in less skilled and experienced workers, thus exacerbating his problems.

By 1894, Alexander’s diaries had become more and more erratic and it was clear that he was suffering great mental torment. Eventually, the workforce, fearing for their lives, mutinied and forced Alexander to abandon the project and arrange passage back to England. The tunnel and shaft were hastily covered up.

Alexander never recovered from his deep disappointment and the shame of failure. His mental health continued to deteriorate until in 1917 he died, insane, in an asylum in Bethnal Green. His papers remained with his family who spent the next century denying their existence…

…until Paul St George, who clearly shares his great-grandfather’s drive and determination, discovered the plans and set out to complete both the tunnel and the Telectroscope and open this astonishing “device for the suppression of absence” to the general public.